Get comfortable.

In 1975, producer Dino De Laurentiis—according to his own recollection, and as recorded for the ages via aggressive PR—was inspired by repeated sightings of a poster of the mighty ape King Kong on his daughter’s bedroom wall. He sensed that the movie-going public was growing weary of gritty realism and thirsted for escapism and fantasy on the big screen.

This, he was certain, would be the perfect vehicle.

Even among the “producer species,” De Laurentiis was above-average in terms of pulling rabbits out of hats. During World War II, and long before he became a “name” in show business, he managed to avoid the front lines via his professional relationship with a colonel he’d met during production of a film they’d worked on in Rome. He was able to shelter at a military hospital for six months; afterwards, he was instructed to appear at another hospital in Naples—where his parents lived, as it happens—and present himself for a new deferment. Just procedure, he was assured. However, upon entering the office, there were German officers present. His paperwork was stamped “Croatia.” He was being sent into battle.

Dino’s boss back in Rome managed to get another sixty days reprieve for “driver De Laurentiis.” After two months, however, Dino had to board a train for Trieste, the last stop before battle. Before he could be shipped out, however, he cornered a high-ranking officer and told him he’d never even held a gun, much less fired one. Instead of making him cannon fodder, a wasted resource, Dino proposed the following: Why not let him utilize his actual experience — he had studied film at Italy’s prestigious il Centro Sperimentale in Rome, after all — and assign him to organize entertainment for the soldiers?

And it worked. He put together variety shows for the troops and stayed out of the trenches. “For those poor guys on the Yugoslavian front, going head to head with Tito’s partisans, it was a relief just to catch a glimpse of ass and hear somebody sing a song,” he later noted.

So, keep that in mind when you ponder De Laurentiis’ rather confident approach to producing a KING KONG remake when the rights to do so were anything but clear.

A Good Idea Has Many Fathers

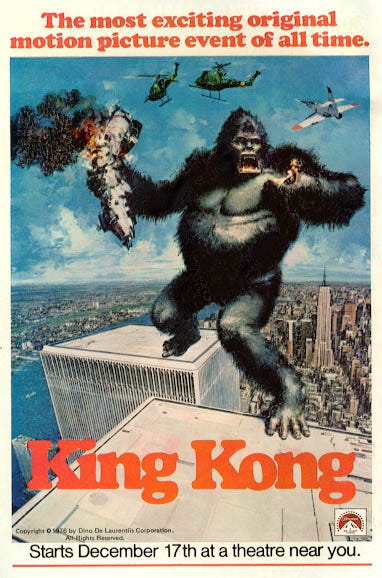

In a meeting with Paramount’s new chairman and CEO Barry Diller (Paramount had been domestic distributor for De Laurentiis-produced films DEATH WISH, MANDINGO, SERPICO and THREE DAYS OF THE CONDOR), the producer expressed his desire to do a blockbuster treatment of the familiar KONG story, making it work as a monster movie, comedy, love story, and fantasy. Diller and Paramount’s parent company, Gulf & Western, gave him the thumbs-up provided he could acquire rights. DeLaurentiis wasted no time in pursuing a signed agreement with RKO-General.

Another version of the story, rendered by Michael Eisner, holds that it was he who got the idea to remake Kong while an executive at ABC. According to Eisner, in December of 1974, he saw King Kong on TV and germinated the notion until unleashing it at a dinner with the president of MCA, Sid Sheinberg, at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Eisner expected no participation or fee; he just wanted to see KONG re-done. Sheinberg seemed unmoved by the idea, so a few days later Eisner made the same pitch to Paramount’s Barry Diller. An enthusiastic Diller then secured De Laurentiis, according to this rendition of the story.

Little did Eisner or Diller know that poker-faced Sheinberg ran with the ball as well, enlisting Universal producers Joe Kerby and Hunt Stromberg, Jr. to get a KONG remake underway. They’d just had huge success with JAWS — why not another giant-monster-runs-amuck? Both studios then began efforts to secure rights to the RKO original at exactly the same time.

Lawyer to the Rescue

Enter attorney Daniel O’Shea, semi-retired and now doing work on commission for RKO. O’Shea’s relationship with RKO went back to the days of the original KING KONG. In fact, as far back as 1935, a letter from O’Shea to John Wharton of the Pioneer Development Corporation (a co-venture of Merian C. Cooper and his wealthy backer, John Hay [Jock] Whitney, who later invested in the development of Technicolor), makes clear O’Shea’s feeling that Cooper had no legal footing for creating additional KONG films independent of RKO. O’Shea’s ongoing legal tending of the KING KONG property—RKO’s biggest asset—led the lawyer to refer to himself as “the zookeeper.”

At this point RKO was a subsidy of General Tire and Rubber, which had acquired the studio’s library of films in 1956 primarily as a means of providing fodder for TV stations they owned across the country. (In 1957, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnez’s Desilu Productions purchased the studio’s facilities to accommodate their television productions, which ended RKO’s ability to produce or distribute films.) RKO was the first major studio to sell such assets into television syndication, and it blazed the trail for the remainder of the studios to follow suit. RKO had re-released KING KONG theatrically—with great success—for the last time in 1956; now it could be seen in living rooms across the country.

The year General Tire acquired the RKO film library, New York’s WOR-TV Channel 9 Million Dollar Movie showed the film, starting on March 5th, sixteen times in a single week—twice nightly and three times per day on the weekend—and set a ratings record.

In his current role, O’Shea had no authority to close deals or sign contracts, but he was the gatekeeper through which Universal and Paramount had to pass in order to lock down KONG rights. As it turns out, both studios met with O’Shea on the same day, both aware that there was another interested party, but neither knowing exactly who they were bidding against.

One thing both Universal and Paramount were apprised of was the fact that Tom O’Neil, chairman of General Tire, desired a percentage of the gross of any KONG film produced. He had, after all, cultivated ongoing interest in the film and character via his television stations and their proliferation of the RKO original. The deal would basically boil down to an up-front cash fee and a back-end piece of the box office. O’Shea was angling $150,000 as the initial payment.

During their lunch meeting, Universal’s Shane put forward, all written up and ready for signatures, an offer of $200,000 in cash and five percent of net profit; Lew Wasserman, chairman of the board of Universal’s parent, MCA, was loath to part with gross. According to Shane’s recollection and testimony, O’Shea carefully read the deal memo, proposed a few acceptable modifications, and said, “That’s fine. We have a deal.”

He did not, however, sign it. (O’Shea would recollect — presumably via deposition, and as reported by Andrew Tobias in a fairly scathing 1976 New York Magazine article — “I did not make any agreement, written or oral…never told him we had an agreement, nor words to that effect…never told him I had the authority to…I am not an employee, agent, or officer of RKO.”)

So, the rights remained in limbo, and both studios forged ahead in their own fashion. It’s only a couple weeks after the initial meetings before Universal and Paramount/Dino become aware of one another’s competing KONG projects. Universal is certain that they have a deal in principle based on their interaction with O’Shea, but De Laurentiis has actual signed paperwork.

Robo-Kong Rises

The same New York Magazine article that detailed O’Shea’s response to both studios’ claims went on to note a report in Variety:

Justified or not, Dino De Laurentiis has created a strong—and sometimes angry—impression among minority actors here that he is looking for an ‘ape-like’ Black actor to play the title role in King Kong. Whatever the intent, it’s undisputed that a number of Black actors were summoned to De Laurentiis’s studio last week where they were introduced to Dino’s son, Frederico, and asked to jump around…”

Indeed, Fredrico had placed an ad in Variety for a “tall, well-built black man” to portray the titular character.

Later, TIME magazine — which was beginning to look like it was auditioning to be part of the Paramount promotion team — reported:

Originally, De Laurentiis planned to use a man in an ape suit for the close-ups of Kong. [But because of the uproar] now he will use a $2-million 40-foot mechanical ape—throughout.”

So, that’s where we got that notion …

Also, TIME reported that the competing Universal version would be presented in Senssurround, “the vibration that made Earthquake so unpleasant.” They’d obviously picked a side.

Dino De Laurentiis was, characteristically, the financial swashbuckler. His offer was $200,000 up front, like Universal’s, but he included three percent of gross profit, escalating to ten percent gross once the movie had earned back two-and-a-half times its budget. Everyone in Hollywood knows “net is for losers”; this was the offer RKO locked down—signed, sealed, and delivered.

De Laurentiis swung a bigger hammer because he—the man who was able to talk himself out of combat by saying he would “put on shows”—was the master of a relatively new way to finance films, which was different than the typical “pitch to a studio and get bankrolled” model prevalent at the time. With a profitable slate of productions behind him, Dino could meet with film distributors in Germany, France, Italy, and other countries and pitch his wares. If they liked what he was selling, Dino would collect a sum of money for rights to exhibit the film in their respective countries. Sometimes these payments would be cash, and sometimes they would be “guarantees.” Dino had enough successes behind him that he would generally collect much more in guarantees than budgeted for the film in question, so he could use the transactions as collateral to borrow the money from banks and pay his contractors. After the film in question was finished, he’d collect from the foreign distributors and pay back his loans.

This innovative financing approach freed De Laurentiis from studio entanglements when it came to casting, script, and crew choices. Whereas the average producer may need to take notes from the head of the studio, Dino entertained no outside instructions or “guidance.”

The intricacies of the dust-up that followed could fill a book in itself; RKO, Paramount, and Universal battled in court over who exactly had rights to a KONG remake while the two studios went ahead with pre-production work, each wanting to be on good footing should they emerge victorious. Paramount/Dino’s position was simple: We signed an agreement with RKO and paid the agreed-upon fee. Universal took a more complicated angle in separate lawsuits, one in state and one in federal court. The state lawsuit argued that they had an agreement in principle with RKO for rights. The federal lawsuit spelled out the reasons they didn’t need any rights to produce a film based on KING KONG.

Universal hung their federal “no rights needed” suit on this sequence of events: Before RKO released the original KING KONG theatrically, a serialized version of the story was published in Mystery Magazine. Since it carried no specific copyright notice, the rights fell to the magazine itself, now long defunct. That makes the KING KONG story public domain, argued Universal, and anyone could produce a motion picture version if they stuck to specific elements in the serialized story and avoided referencing items unique to the 1933 film. In spite of a Los Angeles Superior Court ruling in September of 1975 dismissing Universal’s suit against Paramount, they went forward with pre-production on what they were now calling THE LEGEND OF KING KONG.

Still, observers at the time reasoned that it was not in Universal’s best interests to pursue production of KING KONG given Paramount’s aggressive stance and the fact that RKO had a written agreement with Dino De Laurentiis. This led to speculation that, in spite of the fact that a director had been hired (Joe Sargent, who had helmed THE TAKING OF PELHAM 1 2 3) and Bo Goldman’s script was still being developed, Universal was basically bluffing, setting itself up for a payout.

Full Speed Ahead

Dino, in the meantime, made it very clear to the world that he was making a blockbuster. The man knew how to schmooze.

“I was once on a back lot with six exhibitors,” recalled Larry Gleason, a member of the De Laurentiis production organization for years. “Dino introduced us to talent, showed us how the monkey worked, and told us the whole story. He wrapped it up in typical dramatic fashion by saying….”

… And here comes the “unofficial” tagline….

“….’When the monkey die, everybody cry!’”

Even cynical NEW YORK MAGAZINE is given the red carpet treatment to cover Paramount’s production. Writer Andrew Tobias noted:

With Dino I have been allowed to see everything—heightening my suspicion that he, and he alone, is going through with production of this movie. The original Kong was done with an 18-inch miniatures. De Laurentiis is building a hydraulic, computerized, 40-foot version. After shooting in the studio, the big Kong will be shipped to New York and, De Laurentiis says, lifted by helicopter to the top of the World Trade Center for shooting there.

Later, they enjoy dinner together, where Dino reveals he began thinking in English about a year ago, but nonetheless has five people on staff who translate virtually everything he reads into Italian overnight. (Tobias spends much of the article mocking Dino’s broken English. King Kong is, for instance, “the biggest picture I have never make.”)

None of this literal wining and dining wins Tobias over, however, even after experiencing a fairly stark contrast when visiting Universal. “No one at Universal will talk to me about King Kong.” When he visits Universal Tower in Universal City, he is set up with a public relations woman “who has never even seen the original King Kong, let alone have any poop on the new one.”

His article wraps on January 29th of ’76, when the two companies settle: De Laurentiis gets to make his Kong, and Universal has to wait at least eighteen months to release their version. They also get anywhere from 8% to 11% of the Paramount film’s profits, some merchandising rights, and veto power over sequels.

And the rest is history …

(See a previous examination of the De Laurentiis Kong HERE.)