King Kong: Every Picture Tells a Story

An image you will never look at the same way again...

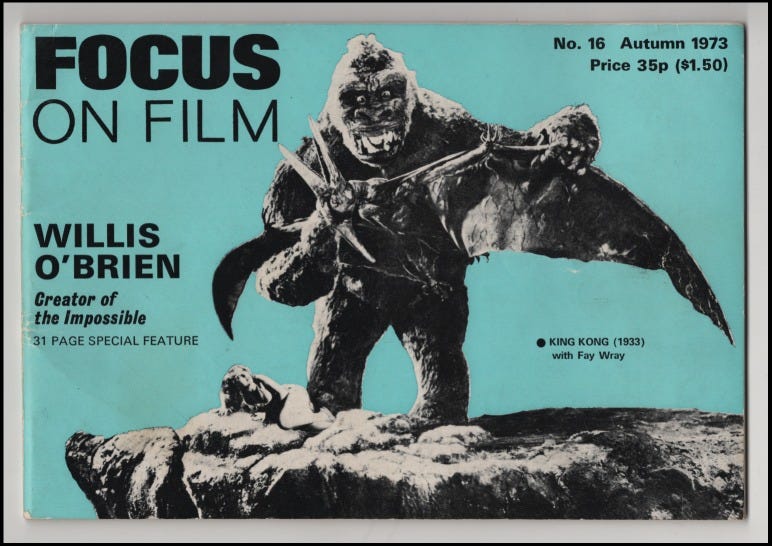

Another piece from The Kong Files, with special thanks to Don Shay, whose stories in Focus on Film and Cinefex magazines first brought to light this tragic tale.

There was scant space between the release in 1933 of King Kong and its sequel, the “seriocomic” Son of Kong, but time enough for almost unimaginable tragedy—and I’m not talking about RKO selling off the Pathe soundstages containing much of the Skull Island jungle set (which necessitated the “Denham and company are immediately chased right off the beach” scene in Son of Kong).

This story begins with a picture:

I’d first seen it on page 43 of George E. Turner and Orville Goldner’s The Making of King Kong (a terrific book which was revelatory for dozens of reasons when first published in the mid-seventies).

The photo intrigued me in all sorts of ways: first, and most obvious, it’s clearly badly torn right through the middle in what seems to be a very purposeful manner; secondly, the person in the photo looks like he’s about to bite the head off of the photographer who’d interrupted him at work—but he’s wearing a hat and tie, as if he’d just walked in off the street or was on his way out.

The caption gives no indication as to the providence of the photo or why it’s damaged.

The subject of the enigmatic photo is master animator Willis O’Brien. Properly describing the importance of this man in making King Kong would require much more space than I’m allotted here, suffice to say that “OBie” arguably represented the heart and soul of the titular character himself.

In animating Kong, OBie conveyed a richness and depth that almost certainly derived from his own background. After seeing Kong’s battle the T-rex, can there be any doubt that OBie was once a pugilist? In the moments before Anne Darrow is attacked by the elasmosaurous in Kong’s cave, you can almost miss a bit of business where the giant gorilla appears to be picking a flower (in contemplation of presenting it to his new bride?).

And, of course, watch Kong’s nuanced final seconds atop the Empire State Building with the following in mind: all OBie had to go on for that scene was this rather succinct scripted action, “He staggers, turns slowly, and topples off roof.”

The Master

O’Brien, who looked the part of the former cowboy and boxer that he was, possessed the ability to inject a spark of life into hours of mundane, back-stiffening, repetitious work, which is what stop motion animation amounted to. The path from idea to actual viewable manifestation was almost comically long and torturous. In the days before instant video playback, O’Brien had to keep straight in his head the action of multiple armatures and scene elements over the course of hours of animating in order to ensure realism in mere moments of film footage. He and his crew wouldn’t know if they’d succeeded until the film was processed – and if something went wrong (a wayward tool in-frame or a blossoming plant, for instance), it was back to the animation table for more hours of tedious manipulation.

O’Brien’s skills were so effective and unprecedented that, in 1922, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was able to utterly fool a group of magicians and journalists – whose very job descriptions include the ability to detect illusion – by projecting footage from The Lost World, featuring OBie’s animated prehistoric beasts. The New York Times noted that the onscreen dinosaurs were “extraordinarily lifelike. If fakes, they were masterpieces.”

There are those who make the case – rather convincingly – that Willis O’Brien deserved a King Kong co-creator credit along with Merian C. Cooper. OBie’s conceptual drawings and work on Creation, the project Cooper cancelled in favor of Kong, almost certainly informed Cooper’s vision of his “giant ape film” and inspired now-classic sequences. Furthermore, most of the visual lynchpins of the production – miniatures combined with humans, stop-motion animation of giant creatures, jungle vistas with astounding depth, incredible attention to detail – are the province of O’Brien and his staff. The film works because OBie and his crew simply invented their way out of problem after problem.

Yet for all of his technical wizardry and soulful manipulation of steel, rubber, and fur, Willis O’Brien seemed destined to be overshadowed by stronger personalities (in the case of Merian Cooper), opportunistic producers (his long-gestating King Kong vs. Frankenstein concept went overseas courtesy of producer John Beck, who sold it as King Kong vs. Godzilla without telling or compensating O’Brien), and broken promises (he had more projects fall apart than you can count on both hands).

The Middle Finger

Which brings us back to the picture.

Willis O’Brien’s first marriage was characteristically impulsive. Hazel Ruth Collette was twelve years younger than Willis when he began dating her, and, through some maneuvering by the girl’s aunt, he found himself fairly trapped into an engagement. The marriage seemed doomed from the beginning; the wild and woolly OBie felt snared, and, perhaps emboldened by his triumph with The Lost World and the financial success and leverage it gained for him, he rebelled with the cad troika: booze, the racetrack, and philandering.

For her part, Hazel exhibited some markedly unbalanced behavior before and after Willis’s indiscretions that, in hindsight, should have served as fair warning of disasters to come.

The uneasy union produced two sons, William and Willis, Jr. By 1930, the couple was effectively separated, though Willis continued to take his beloved boys on various outings. Around 1931, the already troubled Hazel contracted both tuberculosis and cancer, and existed in a near-constant narcotic haze. The elder son, William, developed tuberculosis in one eye and then the other, resulting in complete blindness. The boys remained with their mother, and, while it was by no means an idyllic domestic situation, OBie continued to take them to events like football games, where the younger Willis would do descriptive play-by-play for his older brother.

By fall of 1933, King Kong had been in release for some time and was undeniably a smash hit despite debuting during the throes of America’s Great Depression. OBie, rightfully proud of his achievement, was now charged with capitalizing on Kong’s success with a hurriedly prepared sequel. RKO survived only because of Kong’s phenomenal box office, and would have to do more with less for the foreseeable future in order to regain firm footing.

The much smaller budget for Son of Kong – less than half of its predecessor’s cost – meant that its chief technician, Willis O’Brien, the genius who brought the eighth wonder of the world to unforgettable life, would continue to make the same $300 a week he’d been paid before the groundbreaking KONG startled the world.

Beyond RKO’s financial woes, this situation was indicative of the complicated relationship he had with Merian C. Cooper. The man who proclaimed years afterward that “O’Brien was a genius…Kong is as much his picture as it is mine,” would crow to the same interviewer that, when O’Brien fell ill during the shooting of Kong, Cooper “was forced to work on much of the animation himself” – an utter fabrication that may have served to enthrall a correspondent (in this case, Ron Haver, who related Cooper’s quotes in his book, David O’Selznick’s Hollywood), but belittled O’Brien’s singular and epic talents.

To be sure, Cooper had no need to inflate his own accomplishments. This is a man who:

Hunted Pancho Villa;

As a fighter pilot, was shot down twice;

Was captured two times in wartime, escaping once;

Explored and photographed corners of the world few westerners would dare to visit;

Became one of the earliest investors in modern aviation;

Ran one of the largest studios in Hollywood.

Making a film about a giant gorilla? Just icing on the cake.

Cooper seemed always in ballyhoo mode, however, and could often appear insensitive to the efforts of those with whom he worked in his zeal to captivate a listener or correspondent. The “OBie was out with the flu” story was indeed cute, but the very idea that Cooper could step in for Willis O’Brien at the animating table is the height of absurdity.

To make matters worse, while O’Brien was left largely to his own devices in creating Kong and the techniques that brought Skull Island to life, producers Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack were now familiar enough with some of the processes O’Brien employed that they felt comfortable “adding input” and “making suggestions.” He was uncomfortable with the comic tone of the film, and, when enormous debates arose over matters that would formerly have been resolved simply and autonomously, O’Brien withdrew into a shell and effectively distanced himself from the sequel production. (Can there be any doubt why Denham bandages lil’ Kong’s middle finger in the film?)

OBie’s assistant, Buzz Gibson, is consequently responsible for most of the animation in Son of Kong; the master had largely checked out.

The Son of Kong production was code-named Jamboree in order to dissuade visitors and curious competitors from invading the set; OBie’s techniques were still a mystery to most of the industry, and other studios were anxious to catch up.

In early October, during shooting, O’Brien brought his sons to visit the secret set, allowing sightless William to handle the delicate miniatures. One can imagine how the unique three-dimensional quality of stop-motion animation provided a magical window into the world of Kong and moviemaking for William— it was undoubtedly quite a day for the boys and a tension reliever for their father.

This was very likely OBie’s very last experience with his sons.

Unimaginable Tragedy

Buckle up. It’s about to get very dark.

Later that same week, a neighbor was shocked to hear shots ring out from the home of Hazel O’Brien. When the police arrived they found a nightmare: Hazel lay fully conscious on the service porch floor, a gunshot wound to her chest. Next to her was a .38 revolver with five spent cartridges. William, 14 years-old, lay dead in his bed with two bullets in his chest; 13 year-old Willis, Jr. was found nearby with the same wounds, clinging to life. He would die on the way to the hospital.

Mentally unbalanced and despondent, Hazel had completely unraveled and shot her two sons, then herself. She was quoted in the newspaper as saying, “My husband is not to blame. I just couldn’t sleep and there was no one to leave the kids with.”

She was charged with “suspicion of murder.”

O’Brien was devastated. In a cruel twist of fate, Hazel’s self-inflicted bullet had not only failed to kill her, but actually drained her tubercular lung and may have effectively extended her life. Too ill to prosecute, she remained in the prison ward of Los Angeles General Hospital where she continued to attempt to end her life to no avail. After two years – before being tried for her crimes – she finally succumbed.

Willis O’Brien never visited her.

And the photo? The picture was taken very shortly after the murders, during production of Son of Kong. Imagine the scenario (conjectured, but as likely as any):

OBie, already disillusioned with (and disengaged from) the film, comes in for a meeting or to check some production detail, and is asked – perhaps told – to pose for a quick promotional shot to help hype the movie. Without even removing his hat, ever-game OBie walks up to a nearby model, puts one arm into a white technician’s smock, and turns to the camera.

“Take the damn thing,” he probably spat.

We are told that later, upon being presented with a copy of the photo, OBie was shocked to see the pain etched on his face. He ripped the photo into pieces and handed it back; the print was kept by colleague Marcel Delgado and, many years later, printed (without comment as to its content or condition) in Goldner and Turner’s The Making of King Kong.

Unbelievably, more heartache would follow. After the shooting, O’Brien had begun a relationship with Hazel Rutherford. When diagnosed with advanced breast cancer, she could not face the disfigurement of a radical mastectomy. On the last day of 1933 – mere months after O’Brien buried his murdered sons – Hazel leapt to her death from the seventh floor of the Mayfair Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. She’d tried to reach OBie at his Hollywood Hills home, but, finding him not there, left a note before heading to the hotel.

The tragedy behind the photo and other details of OBie’s life were first brought to my attention via an extraordinary article by Don Shay entitled “Willis O’Brien: Creator of the Impossible,” which I saw in Cinefex magazine (#7, January 1982)1 – an absolute must-read for any fan of King Kong. I’ve paraphrased Shay’s outstanding work above; you’ll want to read his entire article for yourself because, as touched upon earlier, OBie’s travails didn’t end with the murder of his sons or his girlfriend’s suicide.

Fortunately for Willis O’Brien, soon after these events he met and later married Darlyne Prenette, with whom he shared the remainder of his life. The creative frustrations he endured for the balance of his career were likely much easier to endure with her support, and we can hope that he enjoyed some deserved respite after the harrowing events of 1933 – a year of soaring success and devastating calamity for the genius behind King Kong.