You Pulled The Trigger Of My Love Gun, Pt. 3

Before the Fall: A look at the rise of KISS as Kash Kulture - based on an article I wrote in the mid-90s while awaiting a promised (threatened) call from Gene Simmons....

So, as described in Part 1, KISS’s 1976 Destroyer album pretty much ensnared me — not that there was much competition out there. I don’t care what the revisionists say, the fact is this: There was little or nothing emanating from the radio in the mid-seventies to move a pre-teen.

Fleetwood Mac’s output was elevator music; Peter Frampton— beyond using the word “hell” and making his guitar talk(!) in “Do You Feel Like We Do”—was uninspiring; the Rolling Stones were in their flat, bloated Love You Live and Black & Blue period; Led Zeppelin belonged to the slightly older bong-and-van crowd; the folk movement was just too ephemeral to be acknowledged by kids still riding Huffys; and the sex-vibe intrinsic to the emerging and otherwise bothersome disco scene went clear over our pre-pubescent heads.

Then there was KISS.

Here was a foursome on a mission without a shred of pretense, putting it right in our collective face. Long hair a problem for ya, dad? How ‘bout this guy Simmons—yeah, that’s blood all over his face.

Best of all was the mystery; KISS never appeared in public or allowed themselves to be photographed without their makeup. They could claim to be anything they wanted us to believe and play the part with absolute conviction.

We began to take ownership of a new rock mythology. For our pre-teen age group — “Generation X” became the label — rock and roll destruction wasn’t Keith Moon trashing his drum kit; it was Paul Stanley smashing his guitar in time to the beat at the coda of “Rock & Roll All Nite.” Live-on-stage risk-taking wasn’t represented by Janis Joplin and a half-spent bottle of Wild Turkey; it was Gene Simmons belching actual fireballs. In-concert pyrotechnics weren’t Jimi Hendrix’s adventures with Zippo; they were a dizzying array of flashpots and smoke bombs strategically placed around a stage populated by larger than life depictions of the American id. The brash lover, the demonic beast, the demure cat, the spaced spaceman.

Needless to say, I fell headfirst into the KISS mythology along with a substantial portion of that era’s youth. I accumulated their body of work; Destroyer’s successors — Love Gun and Rock & Roll Over — were already in stores, and Alive II was just coming out (my mom was aghast to see that it was a two-album set; “You don’t need that—that’s just ridiculous,” she said ineffectually). My friends and I became regular customers at the local record store1, occasionally making further vinyl investments and staring at the KISS albums we still needed but hadn’t mowed enough lawns to afford. Our bedroom walls became papered with images of the band.

The Merch Marches In

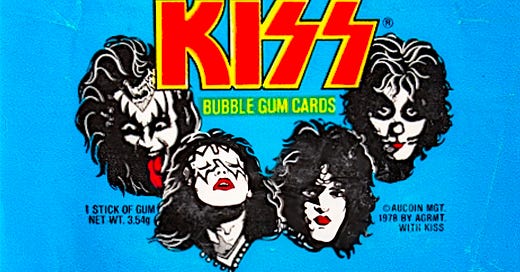

And then a funny thing happened. Around 1977, we began seeing the distinctive KISS lightning-S logo on products other than the normal posters and albums. A new product sighting would be made nearly every week; “Hey, John — I got these trading cards!” a chum would report. My mom—my mom!—brought home KISS notebooks for me to begin the coming school year (this presented a bit of an issue with the nuns at St. Michael’s — were these guys really “Knights in Satan’s Service”?). A reported lunchbox sighting at a department store downtown; next week, kids are totin’ PB&J in a metal box emblazoned with kabuki-themed rock musicians.

Marketing 101

My contemporaries and I stood square in the sights of what was to become one of the most comprehensive marketing efforts ever undertaken by a pre-Batman movie entertainment entity—certainly the most massive such campaign by a rock and roll band.

Paul Stanley admits in his autobiography Face the Music: A Life Exposed, that he and his bandmates were “clueless about merchandising.” Stanley gives credit to the concept of KISS merch to their manager, Bill Aucoin. His first item was an elaborate tour program sold at live shows.

From Stanley’s book:

When I first saw the tour program Bill created for the later stages of the Alive tour, I had never seen anything like it. He never told us he was going to do it. He just showed up one day and said, “Here’s the tour program.” After paging through its twenty-four pages, I thought it was terrific. Bill also thought—and was quickly proved correct—that our fans would want t-shirts and belt buckles. And that was just the tip of the iceberg. He founded an in-house merchandising company together with a guy named Ron Boutwell. Initially, the company fulfilled orders from our fan club. Bill just announced it to us, very matter-of-factly: “We’re going to start marketing merchandise.”

It could not have happened without Bill.

Fans of KISS wanted for nothing as every conceivable variation of tie-in became available. An official fan club, The KISS Army, began producing newsletters and membership kits in 1976. Given their well-established but simple look and persona, KISS lent themselves well to any application from model kits to shoelaces to Colorforms sets.

Critics savaged, then ignored KISS, and radio airplay was minimal at best (the proto-power ballad “Beth” was their lone foothold in many midwestern markets). And they were, as the saying goes, “very big in Japan.”

Despite—or because of—these disadvantages, the band toured doggedly, explosives and smoke machines in tow, establishing themselves as the world’s premier live band. When Casablanca, their label, began experiencing money problems, dedicated band manager Bill Aucoin deployed his American Express card to keep the foursome on the road. They established credibility with metal enthusiasts while maintaining enormous appeal to pre-teens, a development Aucoin noted and exploited to great effect.

Releases subsequent to Destroyer played heavily upon comic book aspects of the band with an eye to “consumer interaction.” 1977’s Love Gun reprised the Ken Kelly heroic-foursome artwork for its cover and came packaged with an actual (paper) “Love Gun” and handy merchandise order form (the form became de rigueur in every release beginning with Destroyer’s immediate follow-up, Rock and Roll Over).

During that same period, owing as much to Gene Simmons’ love of the genre as Bill Aucoin’s marketing insight and Stan Lee’s promotional superpowers, Marvel released a Kiss comic book to which the band members contributed their own blood.

Alive II featured rub-on tattoos; the greatest hits collection Double Platinum packaged already released material and a cardboard “plaque;” and the four simultaneously released solo albums (anthemic Stanley, rootsy Criss, hook-driven Frehley, eclectic Simmons) included interlocking individual comic-art posters.

By the time Unmasked was released in 1980, KISS went right to the heart of the matter with an actual comic strip as cover art. It was a mediocre seller, at best.

In the middle/muddle of all the above, KISS made their network television movie debut in 1978’s KISS Meets the Phantom of the Park (released theatrically in Europe). The movie, broadcast on NBC following Hee Haw, took the KISS concept to its peak; the plot featured the band as super-powered beings who happened to perform rock and roll as a side hack of sorts. Makeup? What makeup?

It was very, very bad (see a deeper look here. If you dare.).

The Beginning of the End

The bloom began to fade as the ‘80s began. Lucrative as their merchandising blitz had become, KISS was losing fans as their chain-store-safe image softened to the point of blandness and a large portion of their fan base aged out of choreographed outrageousness.

I represented an almost perfect “done with KISS” demographic — in 1979, I left grade school and the stuff of childhood behind. In high school, it was suddenly Van Halen, REO Speedwagon, Jimi Hendrix (I read his biography ‘Scuse Me While I Kiss The Sky while serving an in-school suspension, but that’s another story …), Bruce Springsteen, etc.

You know - grown-up stuff.

Also “done with KISS” was Peter Criss, a hard-living devotee of the rock and roll lifestyle, who was was fired from the band (and ejected into obscurity) after micro-minimal participation in his last couple of albums as a member.

Simmons, meanwhile, was expressing dissatisfaction with being typecast as a plodding beast and writing songs about “groupies and getting laid on the road.” Also, he was dating Diana Ross, so he was branching out, to say the least.

Return of the Wizard

With new drummer Eric Carr aboard, KISS needed to shake things up. The decision was made to reunite the band with Bob Ezrin, the producer of Destroyer — and arguably the architect of the band’s sound.

Ezrin agreed to work with KISS again, but only under his stipulations of “total privacy and isolation” with KISS. This was the producer who took the band to stratospheric heights with Destroyer, so, why not let him Svengali another masterpiece into existence?

And, by the way, he proposed a concept album.

And, how did that go?

No one can turn away from a car wreck, so you’ll want to stay tuned for the fourth and final installment of this slice of KISS history …

_____________

I will definitely be writing about the Inner Sleeve of Wausau, Wisconsin, and the proprietor we affectionally referred to as “Mr. Sleeve.”

A fascinating chronicle of the X gen, Mr. Michlig! But obviously you're a man a little out of step with your contemporaries given some of your other proclivities...